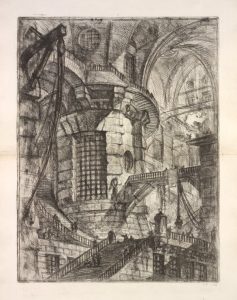

Giovanni Battista Piranesi – The Round Tower

from Carceri d’invenzione.

Part 3: COFFEE AND KAFKA

This stuff is not as easy to write as it seems. As you could discern, I am not big on recording physical detail; but what makes things worse is that I cannot trust my memory about this episode. In the 37 years since my imprisonment I have seen sooo many jailhouse movies that I can no longer be sure whether what I am remembering is actually Regina Coeli or a generic State pen via Hollywood. It should be easy: just try to insert Paul Newman or Sean Penn in that cell, and if you can’t, it must be the real thing, right? Wish it were that easy. The only difference that I can think of with a degree of certainty is cleanliness. RC was way dirtier than any Hollywood jail. And with this caveat we proceed further into uncertainty, line by line.

The cell I was put in did not seem so small (then again, I was from Russia – perhaps it would look like a closet to me now). There were six bunks in two tiers and a small table in between – sort of like a sleeper train compartment, with a toilet hole demurely hidden behind a door. There was even toilet paper! A Soviet could only shake his head at such capitalist excesses.

Looking back, I am still curious how inmates were supposed to take the shower. In the 5 days I spent in Regina Coeli no one would take us out for a shower. At the time it didn’t register because a) in Russia, it was not uncommon to take shower/bath once a week; b) I was expecting to be freed within minutes.

In fact, after I learned of Odessa’s confession, I fully expected to be let go – what was the reason to keep a clearly innocent person locked up? And if the guard had showed up to take us to the showers, I am not sure I would have gone, either: what if I missed the call to go free?

***

The first night’s sleep was, well, brief. Seems like it lasted seconds. A guard banged on the bars: “Caffè!”

“Aw fuck it,” I whispered and turned on the other side.

“Hey! Coffee!” Another inmate patted me on the back. “They won’t serve it again!”

That’s right, I realized, climbing down; this was no Ritz; this was a jail, where one shouldn’t complain but just accept gratefully whatever you are given.

Guess what? Il caffè wasn’t bad. Of course it was light years away from an average coffee in an Italian bar; but it was better than coffee in an average coffee shop in Moscow. Oddly enough, it was just as weak and the amount of milk was comparable, too; it was closer to Moscow than to Rome and created more confusion in my head. Perhaps the previous weeks, with flying to Vienna and riding a train to Rome, were a dream, and somehow I got stuck in no-man’s land between Russia and Italy. Fellow cellmates were bad actors; especially when I realized that they spoke Italian poorly, with atrocious accents – compared to them, I was a total professore.

Anyway, scalding hot, il caffè hit the spot. Later I was to discover that coffee delivery – it was ladled from a large urn into our tin mugs – was actually the only reliable meal of the day. Everything else was perfectly unpredictable. Some days the kitchen was in such a rush that food was delivered every hour and the whole daily ration was wrapped up by noon. Huge steaming helpings of pasta e fagioli (a staple) could arrive at nine, followed by fruit (another staple) an hour later, chicken another hour later, and bread and cheese around noon – and that was that for the day. “Maybe they got an outside job catering a wedding or something,” my cellmate Sergio would say. “Chissa?” Who knows?

Other days there were big helpings in the morning and nothing till late afternoon. Unspoiled by Russian food, I found the prison diet eminently edible, but my stomach was going nuts. We didn’t have lockers, so even if I wanted to hold on to some food for later, it was not realistic. Plus what if another inmate made a claim on my leftovers? I wasn’t sure about the proper protocol and didn’t want to find out. The stomach had to adjust.

We were in this together – everyone polished his plate clean. Everyone but Sergio, that is. Sergio was a perfect picture of a spoiled Italian boy who could not even conceive of eating all this stronzo and subsisted solely on homemade food that his mamma brought him every day. He was not particularly forthcoming with it – we got his share of jail food, wasn’t that generous enough?

I had another interrogation, a word-for-word copy of the first one: Was asleep, didn’t see anything.

“But you already know I wasn’t the one who did it”, I added; “so why are you keeping me here?”

“Eh…” The interrogator made that universal Italian gesture of shrugging and pushing his chin up and forward. The combination can mean anything in different contexts, but most commonly is close to New York’s “fuhgeddaboudit” (which is just as varied): What can you do, just write it off, that’s how life is –

The more I look back, the less I understand myself. I was about two weeks out of Russia, where, in view of 1,000 humiliations visited upon an average citizen daily, “writing it off” was key to emotional survival – why was I so enraged by this petty official’s lack of concern? In fact, he simply didn’t care, which was a big improvement on Russia, where an official could reward your persistence with getting really vicious (still do it, I am told). So what was the big deal? Ah, the West, the blinding neon of Coca Cola and civil justice, all so hard to resist. I should have been smarter and taken the Moscow quality of morning coffee as an early cue.

“Paperwork,” he said; “you know, papers go back and forth… disgusting, isn’t it? Italia, che bel casino… You are lucky you don’t live in this country; you know what happened when my mother-in-law’s plumbing got busted?” (hands go up, loud exhale). What we went through with this goddamn city bureaucracy. You are lucky you are here – we ain’t so bad.”

I forced an expression of empathy – eh, mother-in-law, who can’t relate to that. “So when do you think…?”

Another sigh, hands spread wide: Who knows? “Now if you had someone on the outside who could post bail…”

I shook my head. I did have a couple of phone numbers in Salerno, but I was ashamed to call. They were not family or even close – how could I impose?

“This has to go to the judge, and judges have their calendars. But they are also human, they have their lives, you know? In Italia, we love life, and there’s more to life than judging, eh? So who knows? It could be over tomorrow. Or it could take longer.”

That was a great closing remark, I thought, strolling back to the cell, afraid of getting lost and being charged with attempted escape. The guard who was supposed to take me back had stopped to discuss yesterday’s dismal performance by the Lazio team and forgot all about me. Really, I could be released tomorrow – the glass is half-full – or “who knows” – the glass is half-empty. It was really up to me.

And so I kept waiting; and some of my cellmates were even worse off than I was, I came to learn.

BACK

NEXT